-

21 девон

-

22 Девон

-

23 Medical Huck

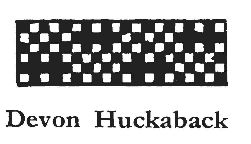

DEVON, or MEDICAL HUCKThis is the simplest form of huckaback weave, and is on 10 ends and 6 picks. The warp threads are usually dented three and two per dent alternately, which tends to prevent the threads splitting in the cloth and forming cracks. Woven with two picks in a shed. Woven about 58 ends and 30 double picks per inch, from 30's and 26's linen yarns, 25-in. wide cloth. Another cloth is made 26-in. wide, reed 30 porter (two and three threads alternately), reed width 281/2-in., warp 3-lb. flax (331/3 per cent loss), weft 4-lb. flax (331/3 per cent loss), 24 double shots on 37/40-in. glass, laid 111 yards, loom length 95 yards, finished length, 102 yards. These details are as usually used in the trade ————————

Also known as Devon Huck.

————————

Also known as Devon Huck. -

24 Остров Девон

-

25 Девон (Девоншир)

Философский камень, Названия местРусско-английский словарь Гарри Поттер (Народный перевод) > Девон (Девоншир)

-

26 Девон (Девоншир)

Философский камень, Названия местРусско-английский словарь Гарри Поттер (Народный перевод) > Девон (Девоншир)

-

27 Devono

Devon, Devonian period -

28 Девон

Geography: Devon, (граф.) Devon (Англия, Великобритания), (о.) Devon Island (Канадский Арктический арх., Канада) -

29 девон

Geography: Devon, (граф.) Devon (Англия, Великобритания), (о.) Devon Island (Канадский Арктический арх., Канада) -

30 Churchward, George Jackson

[br]b. 31 January 1857 Stoke Gabriel, Devon, Englandd. 19 December 1933 Swindon, Wiltshire, England[br]English mechanical engineer who developed for the Great Western Railway a range of steam locomotives of the most advanced design of its time.[br]Churchward was articled to the Locomotive Superintendent of the South Devon Railway in 1873, and when the South Devon was absorbed by the Great Western Railway in 1876 he moved to the latter's Swindon works. There he rose by successive promotions to become Works Manager in 1896, and in 1897 Chief Assistant to William Dean, who was Locomotive Carriage and Wagon Superintendent, in which capacity Churchward was allowed extensive freedom of action. Churchward eventually succeeded Dean in 1902: his title changed to Chief Mechanical Engineer in 1916.In locomotive design, Churchward adopted the flat-topped firebox invented by A.J.Belpaire of the Belgian State Railways and added a tapered barrel to improve circulation of water between the barrel and the firebox legs. He designed valves with a longer stroke and a greater lap than usual, to achieve full opening to exhaust. Passenger-train weights had been increasing rapidly, and Churchward produced his first 4–6– 0 express locomotive in 1902. However, he was still developing the details—he had a flair for selecting good engineering practices—and to aid his development work Churchward installed at Swindon in 1904 a stationary testing plant for locomotives. This was the first of its kind in Britain and was based on the work of Professor W.F.M.Goss, who had installed the first such plant at Purdue University, USA, in 1891. For comparison with his own locomotives Churchward obtained from France three 4–4–2 compound locomotives of the type developed by A. de Glehn and G. du Bousquet. He decided against compounding, but he did perpetuate many of the details of the French locomotives, notably the divided drive between the first and second pairs of driving wheels, when he introduced his four-cylinder 4–6–0 (the Star class) in 1907. He built a lone 4–6–2, the Great Bear, in 1908: the wheel arrangement enabled it to have a wide firebox, but the type was not perpetuated because Welsh coal suited narrow grates and 4–6–0 locomotives were adequate for the traffic. After Churchward retired in 1921 his successor, C.B.Collett, was to enlarge the Star class into the Castle class and then the King class, both 4–6–0s, which lasted almost as long as steam locomotives survived in service. In Church ward's time, however, the Great Western Railway was the first in Britain to adopt six-coupled locomotives on a large scale for passenger trains in place of four-coupled locomotives. The 4–6–0 classes, however, were but the most celebrated of a whole range of standard locomotives of advanced design for all types of traffic and shared between them many standardized components, particularly boilers, cylinders and valve gear.[br]Further ReadingH.C.B.Rogers, 1975, G.J.Churchward. A Locomotive Biography, London: George Allen \& Unwin (a full-length account of Churchward and his locomotives, and their influence on subsequent locomotive development).C.Hamilton Ellis, 1958, Twenty Locomotive Men, Shepperton: Ian Allan, Ch. 20 (a good brief account).Sir William Stanier, 1955, "George Jackson Churchward", Transactions of the NewcomenSociety 30 (a unique insight into Churchward and his work, from the informed viewpoint of his former subordinate who had risen to become Chief Mechanical Engineer of the London, Midland \& Scottish Railway).PJGRBiographical history of technology > Churchward, George Jackson

-

31 Newcomen, Thomas

SUBJECT AREA: Steam and internal combustion engines[br]b. January or February 1663 Dartmouth, Devon, Englandd. 5 August 1729 London, England[br]English inventor and builder of the world's first successful stationary steam-engine.[br]Newcomen was probably born at a house on the quay at Dartmouth, Devon, England, the son of Elias Newcomen and Sarah Trenhale. Nothing is known of his education, and there is only dubious evidence of his apprenticeship to an ironmonger in Exeter. He returned to Dartmouth and established himself there as an "ironmonger". The term "ironmonger" at that time meant more than a dealer in ironmongery: a skilled craftsman working in iron, nearer to today's "blacksmith". In this venture he had a partner, John Calley or Caley, who was a plumber and glazier. Besides running his business in Dartmouth, it is evident that Newcomen spent a good deal of time travelling round the mines of Devon and Cornwall in search of business.Eighteenth-century writers and others found it impossible to believe that a provincial ironmonger could have invented the steam-engine, the concept of which had occupied the best scientific brains in Europe, and postulated a connection between Newcomen and Savery or Papin, but scholars in recent years have failed to find any evidence of this. Certainly Savery was in Dartmouth at the same time as Newcomen but there is nothing to indicate that they met, although it is possible. The most recent biographer of Thomas Newcomen is of the opinion that he was aware of Savery and his work, that the two men had met by 1705 and that, although Newcomen could have taken out his own patent, he could not have operated his own engines without infringing Savery's patent. In the event, they came to an agreement by which Newcomen was enabled to sell his engines under Savery's patent.The first recorded Newcomen engine is dated 1712, although this may have been preceded by a good number of test engines built at Dartmouth, possibly following a number of models. Over one hundred engines were built to Newcomen's design during his lifetime, with the first engine being installed at the Griff Colliery near Dudley Castle in Staffordshire.On the death of Thomas Savery, on 15 May 1715, a new company, the Proprietors of the Engine Patent, was formed to carry on the business. The Company was represented by Edward Elliot, "who attended the Sword Blade Coffee House in Birchin Lane, London, between 3 and 5 o'clock to receive enquiries and to act as a contact for the committee". Newcomen was, of course, a member of the Proprietors.A staunch Baptist, Newcomen married Hannah Waymouth, who bore him two sons and a daughter. He died, it is said of a fever, in London on 5 August 1729 and was buried at Bunhill Fields.[br]Further ReadingL.T.C.Rolt and J.S.Allen, 1977, The Steam Engine of Thomas Newcomen, Hartington: Moorland Publishing Company (the definitive account of his life and work).IMcN -

32 Hügel

m1. barrow2. hill3. mound4. tumuluspl1. hills2. mounds1. torr Br. (Devon)2. tor Br. (Devon) -

33 carretera de circunvalación

ring road* * *(n.) = bypass, ring roadEx. The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.Ex. He lived in a tent pitched on the central reservation of the Wolverhampton ring road for over 30 years.* * *(n.) = bypass, ring roadEx: The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.

Ex: He lived in a tent pitched on the central reservation of the Wolverhampton ring road for over 30 years.* * *beltway, Brring road -

34 circunvalación

f.1 ring road, circumvallation, encirclement, speedway.2 circumvolution.* * *1 (carretera) ring road\* * *SFcarretera de circunvalación — ring road, bypass, beltway (EEUU)

* * *= bypass, ring road.Ex. The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.Ex. He lived in a tent pitched on the central reservation of the Wolverhampton ring road for over 30 years.----* carretera de circunvalación = bypass, ring road.* ronda de circunvalación = ring road, bypass.* * *= bypass, ring road.Ex: The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.

Ex: He lived in a tent pitched on the central reservation of the Wolverhampton ring road for over 30 years.* carretera de circunvalación = bypass, ring road.* ronda de circunvalación = ring road, bypass.* * *un autobús de circunvalación a bus which does a circular route* * *1. [acción] going round2. [carretera] Br ring road, US beltway* * *f:(carretera de) circunvalación beltway, Br ring road* * *carretera de circunvalación: bypass, beltway -

35 pasar por la mitad de

(v.) = cut throughEx. The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.* * *(v.) = cut throughEx: The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.

-

36 ronda de circunvalación

(n.) = ring road, bypassEx. He lived in a tent pitched on the central reservation of the Wolverhampton ring road for over 30 years.Ex. The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon.* * *(n.) = ring road, bypassEx: He lived in a tent pitched on the central reservation of the Wolverhampton ring road for over 30 years.

Ex: The author discusses the controversy over the construction of a bypass which cuts through a national park in Devon. -

37 Девон

I( Канада) DevonIIо-в (Канада) Devon Island -

38 Brunel, Isambard Kingdom

SUBJECT AREA: Civil engineering, Land transport, Mechanical, pneumatic and hydraulic engineering, Ports and shipping, Public utilities, Railways and locomotives[br]b. 9 April 1806 Portsea, Hampshire, Englandd. 15 September 1859 18 Duke Street, St James's, London, England[br]English civil and mechanical engineer.[br]The son of Marc Isambard Brunel and Sophia Kingdom, he was educated at a private boarding-school in Hove. At the age of 14 he went to the College of Caen and then to the Lycée Henri-Quatre in Paris, after which he was apprenticed to Louis Breguet. In 1822 he returned from France and started working in his father's office, while spending much of his time at the works of Maudslay, Sons \& Field.From 1825 to 1828 he worked under his father on the construction of the latter's Thames Tunnel, occupying the position of Engineer-in-Charge, exhibiting great courage and presence of mind in the emergencies which occurred not infrequently. These culminated in January 1828 in the flooding of the tunnel and work was suspended for seven years. For the next five years the young engineer made abortive attempts to find a suitable outlet for his talents, but to little avail. Eventually, in 1831, his design for a suspension bridge over the River Avon at Clifton Gorge was accepted and he was appointed Engineer. (The bridge was eventually finished five years after Brunel's death, as a memorial to him, the delay being due to inadequate financing.) He next planned and supervised improvements to the Bristol docks. In March 1833 he was appointed Engineer of the Bristol Railway, later called the Great Western Railway. He immediately started to survey the route between London and Bristol that was completed by late August that year. On 5 July 1836 he married Mary Horsley and settled into 18 Duke Street, Westminster, London, where he also had his office. Work on the Bristol Railway started in 1836. The foundation stone of the Clifton Suspension Bridge was laid the same year. Whereas George Stephenson had based his standard railway gauge as 4 ft 8½ in (1.44 m), that or a similar gauge being usual for colliery wagonways in the Newcastle area, Brunel adopted the broader gauge of 7 ft (2.13 m). The first stretch of the line, from Paddington to Maidenhead, was opened to traffic on 4 June 1838, and the whole line from London to Bristol was opened in June 1841. The continuation of the line through to Exeter was completed and opened on 1 May 1844. The normal time for the 194-mile (312 km) run from Paddington to Exeter was 5 hours, at an average speed of 38.8 mph (62.4 km/h) including stops. The Great Western line included the Box Tunnel, the longest tunnel to that date at nearly two miles (3.2 km).Brunel was the engineer of most of the railways in the West Country, in South Wales and much of Southern Ireland. As railway networks developed, the frequent break of gauge became more of a problem and on 9 July 1845 a Royal Commission was appointed to look into it. In spite of comparative tests, run between Paddington-Didcot and Darlington-York, which showed in favour of Brunel's arrangement, the enquiry ruled in favour of the narrow gauge, 274 miles (441 km) of the former having been built against 1,901 miles (3,059 km) of the latter to that date. The Gauge Act of 1846 forbade the building of any further railways in Britain to any gauge other than 4 ft 8 1/2 in (1.44 m).The existence of long and severe gradients on the South Devon Railway led to Brunel's adoption of the atmospheric railway developed by Samuel Clegg and later by the Samuda brothers. In this a pipe of 9 in. (23 cm) or more in diameter was laid between the rails, along the top of which ran a continuous hinged flap of leather backed with iron. At intervals of about 3 miles (4.8 km) were pumping stations to exhaust the pipe. Much trouble was experienced with the flap valve and its lubrication—freezing of the leather in winter, the lubricant being sucked into the pipe or eaten by rats at other times—and the experiment was abandoned at considerable cost.Brunel is to be remembered for his two great West Country tubular bridges, the Chepstow and the Tamar Bridge at Saltash, with the latter opened in May 1859, having two main spans of 465 ft (142 m) and a central pier extending 80 ft (24 m) below high water mark and allowing 100 ft (30 m) of headroom above the same. His timber viaducts throughout Devon and Cornwall became a feature of the landscape. The line was extended ultimately to Penzance.As early as 1835 Brunel had the idea of extending the line westwards across the Atlantic from Bristol to New York by means of a steamship. In 1836 building commenced and the hull left Bristol in July 1837 for fitting out at Wapping. On 31 March 1838 the ship left again for Bristol but the boiler lagging caught fire and Brunel was injured in the subsequent confusion. On 8 April the ship set sail for New York (under steam), its rival, the 703-ton Sirius, having left four days earlier. The 1,340-ton Great Western arrived only a few hours after the Sirius. The hull was of wood, and was copper-sheathed. In 1838 Brunel planned a larger ship, some 3,000 tons, the Great Britain, which was to have an iron hull.The Great Britain was screwdriven and was launched on 19 July 1843,289 ft (88 m) long by 51 ft (15.5 m) at its widest. The ship's first voyage, from Liverpool to New York, began on 26 August 1845. In 1846 it ran aground in Dundrum Bay, County Down, and was later sold for use on the Australian run, on which it sailed no fewer than thirty-two times in twenty-three years, also serving as a troop-ship in the Crimean War. During this war, Brunel designed a 1,000-bed hospital which was shipped out to Renkioi ready for assembly and complete with shower-baths and vapour-baths with printed instructions on how to use them, beds and bedding and water closets with a supply of toilet paper! Brunel's last, largest and most extravagantly conceived ship was the Great Leviathan, eventually named The Great Eastern, which had a double-skinned iron hull, together with both paddles and screw propeller. Brunel designed the ship to carry sufficient coal for the round trip to Australia without refuelling, thus saving the need for and the cost of bunkering, as there were then few bunkering ports throughout the world. The ship's construction was started by John Scott Russell in his yard at Millwall on the Thames, but the building was completed by Brunel due to Russell's bankruptcy in 1856. The hull of the huge vessel was laid down so as to be launched sideways into the river and then to be floated on the tide. Brunel's plan for hydraulic launching gear had been turned down by the directors on the grounds of cost, an economy that proved false in the event. The sideways launch with over 4,000 tons of hydraulic power together with steam winches and floating tugs on the river took over two months, from 3 November 1857 until 13 January 1858. The ship was 680 ft (207 m) long, 83 ft (25 m) beam and 58 ft (18 m) deep; the screw was 24 ft (7.3 m) in diameter and paddles 60 ft (18.3 m) in diameter. Its displacement was 32,000 tons (32,500 tonnes).The strain of overwork and the huge responsibilities that lay on Brunel began to tell. He was diagnosed as suffering from Bright's disease, or nephritis, and spent the winter travelling in the Mediterranean and Egypt, returning to England in May 1859. On 5 September he suffered a stroke which left him partially paralysed, and he died ten days later at his Duke Street home.[br]Further ReadingL.T.C.Rolt, 1957, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, London: Longmans Green. J.Dugan, 1953, The Great Iron Ship, Hamish Hamilton.IMcNBiographical history of technology > Brunel, Isambard Kingdom

-

39 Froude, William

SUBJECT AREA: Ports and shipping[br]b. 1810 Dartington, Devon, Englandd. 4 May 1879 Simonstown, South Africa[br]English naval architect; pioneer of experimental ship-model research.[br]Froude was educated at a preparatory school at Buckfastleigh, and then at Westminster School, London, before entering Oriel College, Oxford, to read mathematics and classics. Between 1836 and 1838 he served as a pupil civil engineer, and then he joined the staff of Isambard Kingdom Brunel on various railway engineering projects in southern England, including the South Devon Atmospheric Railway. He retired from professional work in 1846 and lived with his invalid father at Dartington Parsonage. The next twenty years, while apparently unproductive, were important to Froude as he concentrated his mind on difficult mathematical and scientific problems. Froude married in 1839 and had five children, one of whom, Robert Edmund Froude (1846–1924), was to succeed him in later years in his research work for the Admiralty. Following the death of his father, Froude moved to Paignton, and there commenced his studies on the resistance of solid bodies moving through fluids. Initially these were with hulls towed through a house roof storage tank by wires taken over a pulley and attached to falling weights, but the work became more sophisticated and was conducted on ponds and the open water of a creek near Dartmouth. Froude published work on the rolling of ships in the second volume of the Transactions of the then new Institution of Naval Architects and through this became acquainted with Sir Edward Reed. This led in 1870 to the Admiralty's offer of £2,000 towards the cost of an experimental tank for ship models at Torquay. The tank was completed in 1872 and tests were carried out on the model of HMS Greyhound following full-scale towing trials which had commenced on the actual ship the previous year. From this Froude enunciated his Law of Comparisons, which defines the rules concerning the relationship of the power required to move geometrically similar floating bodies across fluids. It enabled naval architects to predict, from a study of a much less expensive and smaller model, the resistance to motion and the power required to move a full-size ship. The work in the tank led Froude to design a model-cutting machine, dynamometers and machinery for the accurate ruling of graph paper. Froude's work, and later that of his son, was prodigious and covered many fields of ship design, including powering, propulsion, rolling, steering and stability. In only six years he had stamped his academic authority on the new science of hydrodynamics, served on many national committees and corresponded with fellow researchers throughout the world. His health suffered and he sailed for South Africa to recuperate, but he contracted dysentery and died at Simonstown. He will be remembered for all time as one of the greatest "fathers" of naval architecture.[br]Principal Honours and DistinctionsFRS. Honorary LLD Glasgow University.Bibliography1955, The Papers of William Froude, London: Institution of Naval Architects (the Institution also published a memoir by Sir Westcott Abell and an evaluation of his work by Dr R.W.L. Gawn of the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors; this volume reprints all Froude's papers from the Institution of Naval Architects and other sources as diverse as the British Association, the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Institution of Civil Engineers.Further ReadingA.T.Crichton, 1990, "William and Robert Edmund Froude and the evolution of the ship model experimental tank", Transactions of the Newcomen Society 61:33–49.FMW -

40 Heaviside, Oliver

[br]b. 18 May 1850 London, Englandd. 2 February 1925 Torquay, Devon, England[br]English physicist who correctly predicted the existence of the ionosphere and its ability to reflect radio waves.[br]Brought up in poor, almost Dickensian, circumstances, at the age of 13 years Heaviside, a nephew by marriage of Sir Charles Wheatstone, went to Camden House Grammar School. There he won a medal for science, but he was forced to leave because his parents could not afford the fees. After a year of private study, he began his working life in Newcastle in 1870 as a telegraph operator for an Anglo-Dutch cable company, but he had to give up after only four years because of increasing deafness. He therefore proceeded to spend his time studying theoretical aspects of electrical transmission and communication, and moved to Devon with his parents in 1889. Because the operation of many electrical circuits involves transient phenomena, he found it necessary to develop what he called operational calculus (which was essentially a form of the Laplace transform calculus) in order to determine the response to sudden voltage and current changes. In 1893 he suggested that the distortion that occurred on long-distance telephone lines could be reduced by adding loading coils at regular intervals, thus creating a matched-transmission line. Between 1893 and 1912 he produced a series of writings on electromagnetic theory, in one of which, anticipating a conclusion of Einstein's special theory of relativity, he put forward the idea that the mass of an electric charge increases with its velocity. When it was found that despite the curvature of the earth it was possible to communicate over very great distances using radio signals in the so-called "short" wavebands, Heaviside suggested the presence of a conducting layer in the ionosphere that reflected the waves back to earth. Since a similar suggestion had been made almost at the same time by Arthur Kennelly of Harvard, this layer became known as the Kennelly-Heaviside layer.[br]Principal Honours and DistinctionsFRS 1891. Institution of Electrical Engineers Faraday Medal 1924. Honorary PhD Gottingen. Honorary Member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.Bibliography1872. "A method for comparing electro-motive forces", English Mechanic (July).1873. Philosophical Magazine (February) (a paper on the use of the Wheatstone Bridge). 1889, Electromagnetic Waves.1892, Electrical Papers.1893–1912, Electromagnetic Theory.Further ReadingI.Catt (ed.), 1987, Oliver Heaviside, The Man, St Albans: CAM Publishing.P.J.Nahin, 1988, Oliver Heaviside, Sage in Solitude: The Life and Works of an Electrical Genius of the Victorian Age, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, New York.J.B.Hunt, The Maxwellians, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.See also: Appleton, Sir Edward VictorKF

См. также в других словарях:

devon — devon … Dictionnaire des rimes

Devon — bezeichnet: Devon (Geologie), eine geologische Formation bzw. ein Zeitalter Devon (Vorname), einen männlichen Vornamen Devon ist der Name folgender geographischer Objekte: Devon (England), eine englische Grafschaft Devon (Nova Scotia), Kanada… … Deutsch Wikipedia

devon — [ devɔ̃ ] n. m. • 1907; mot angl., du comté de Devonshire ♦ Pêche Appât articulé ayant l aspect d un poisson, d un insecte, etc., et qui est muni de plusieurs hameçons. On écrirait mieux dévon. ● devon nom masculin (de Devon, nom propre) Leurre… … Encyclopédie Universelle

devon — DEVÓN, devoni, s.m. Peştişor artificial de metal prevăzut cu cârlige, care serveşte ca momeală la prinderea peştilor răpitori. – Din fr. devon. Trimis de IoanSoleriu, 17.07.2004. Sursa: DEX 98 devón s. m. Trimis de siveco, 10.08.2004. Sursa:… … Dicționar Român

Devon 30 — Administration Pays Canada Province … Wikipédia en Français

Devon — Berwyn, PA U.S. Census Designated Place in Pennsylvania Population (2000): 5067 Housing Units (2000): 2035 Land area (2000): 2.498379 sq. miles (6.470772 sq. km) Water area (2000): 0.000000 sq. miles (0.000000 sq. km) Total area (2000): 2.498379… … StarDict's U.S. Gazetteer Places

Devon, PA — Devon Berwyn, PA U.S. Census Designated Place in Pennsylvania Population (2000): 5067 Housing Units (2000): 2035 Land area (2000): 2.498379 sq. miles (6.470772 sq. km) Water area (2000): 0.000000 sq. miles (0.000000 sq. km) Total area (2000):… … StarDict's U.S. Gazetteer Places

Devon — De von, n. One of a breed of hardy cattle originating in the country of Devon, England. Those of pure blood have a deep red color. The small, longhorned variety, called North Devons, is distinguished by the superiority of its working oxen. [1913… … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

Devon [1] — Devon (Dewwʼn), engl. Grafschaft am Kanale mit 580000 E. auf 122 QM.; sie ist gebirgig, hat Bergbau auf Silber, Kupfer, Zinn, Eisen, Blei, Granit, Kalk und Schiefer, liefert Wollentuch und Spitzen, Eisenwaaren, hat Schiffsbau und Fischerei. Von… … Herders Conversations-Lexikon

Devon — Devon1 [dev′ən] n. any of a breed of medium sized, red beef cattle, originally raised in the area of Devon, England Devon2 [dev′ən] 1. island of the Arctic Archipelago, north of Baffin region of Nunavut, Canada: 20,861 sq mi (54,030 sq km) 2.… … English World dictionary

Devon — (spr. Dewwen), 1) (Devonshire, spr. Dewwenschirr), Grafschaft auf der südwestlichen Landzunge von England, 122,17 QM.; grenzt an den Bristol Kanal (Atlantischer Ocean), an die Grafschaft Cornwall, an den Kanal (la Manche), an die Grafschaften… … Pierer's Universal-Lexikon